GEORGE Magazine

Vol. I, No. 2 (Dec 1996)

pp. 94, 96, 98

The Quigley Cult

What do President Bill Clinton and the militias have in common?

They both revere the weird theories of the late Carroll Quigley.

By Scott McLamee

During his second semester at Georgetown University, Bill Clinton did a bold thing.

He skipped classes. More to the point, he missed four sessions of

Development of

Civilization, a yearlong course for students entering the School for Foreign Service,

taught by Professor Carroll Quigley.

Quigley was something of a legend, and not just at the university. He lectured at the Brookings

Institution and at the Industrial College of the Armed Forces. He wrote for the

Washington Post

and the Star, the now-defunct D.C. daily newspaper. And the talks he gave at the State Department

on Africa and France were worked up into articles for the magazine

Current History, where Quigley

served on the editorial board. He was a consultant to the House Committee on Astronautics and

Space Exploration and had some connection with the birth of NASA. His work even caught the

attention of Herman Kahn, the consummate policy wonk of the late '50s and early ‘60s, who was then

thinking deep thoughts on thermonuclear war, and scaring people to death in the process.

(Future) President Bill Clinton

In the classroom, Professor Quigley himself inspired a kind of dread. His lectures were dramatic

performances, and his exams terrified generations of freshmen at Georgetown. Nearly half of the

176 students who enrolled alongside Bill Clinton scored a D or below for the fall 1964 semester.

In Professor Quigley's hands, the study of Western Civilization was a demanding activity for all

parties involved. "I'm in the business of teaching people how to think," Quigley liked to say,

"of training executives and not clerks."

But it was also part of the Quigley legend — the substance of generations of undergraduate rumor —

that you could survive his course by conscientiously learning and reciting back his ideas. Of course,

university students have been saying that kind of thing about their professors for about a thousand

years, sometimes justly, sometimes not. But Quigley had indeed worked out his own theory of history,

with its own jargon, and this was worth knowing. When an exam question asked, "How does a civilization

decline and fall?” — as the first exam for the fall 1964 semester did — it would have been prudent to

form one's answer by invoking the Quigleyan principle of "the institutionalization of the instrument."

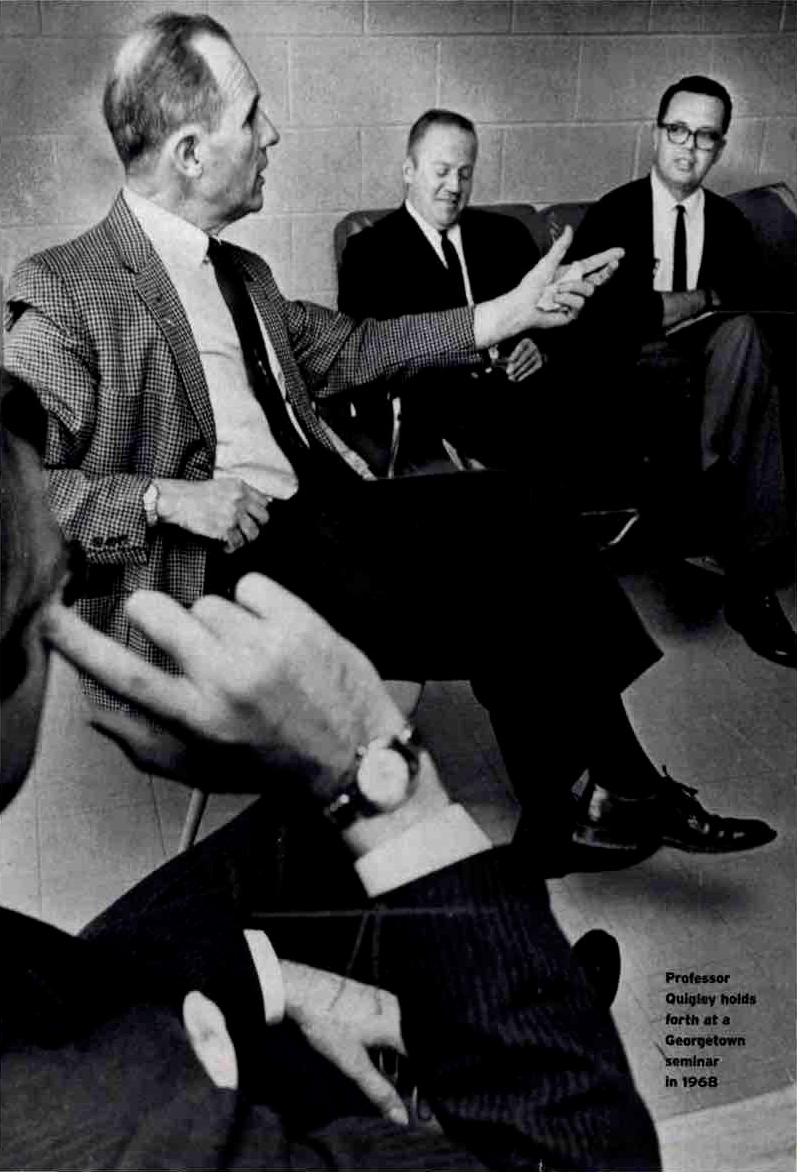

"Professor Quigley holds forth at a Georgetown seminar in 1968"

Bill Clinton, it seems, mastered basic Quigleyism in rapid order. Friends

recall that he would stay behind after class with a clutch of students who threw

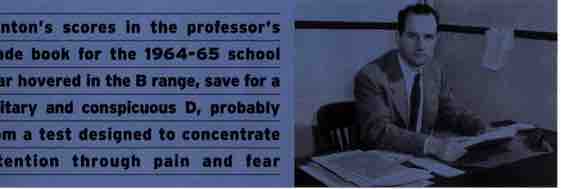

questions at the professor. The scores in the professor's grade book for the

1964 - 65 school year (preserved, like the rest of Quigley's papers, at the Georgetown

University library) form a row of figures hovering steadily in the B range for Clinton —

save for a solitary and conspicuous D, probably from a test early that semester designed

to concentrate students' attention through pain and fear. Overall, Clinton got a B for

both parts of the course, and the sharp rise of absences in the second semester

(he missed only one class in the fall) might indicate a certain degree of confidence in

grasping the art of testmanship under the Quigley regime.

In books on the President that have appeared since 1992, discussions of Quigley are scarce

and always brief. They seldom note more than his transit across the young president-to-be's

path. But Clinton himself often recalled the professor in his speeches.

(Quigley died in the first days of 1977 — too soon to see his former student elected to office).

Clinton mentioned him in his first inaugural speech as governor of Arkansas.

He spoke of Quigley at Georgetown University in 1991, while launching his presidential bid.

And so it should have been of little surprise that in accepting the presidential nomination at

the Democratic National Convention in 1992, Clinton once again invoked the professor:

"As a teenager, I heard John Kennedy's summons to citizenship. And then, as a student at

Georgetown, I heard that call clarified by a professor I had, named Carroll Quigley, who said

that America was the greatest nation in history because our people have always believed in two

great ideas: That tomorrow can be better than today and that each of us has a personal, moral

responsibility to make it so."

_________________________________________________________________

"Carroll Quigley sitting at his desk at Georgetown University"

_________________________________________________________________

This (in its most sound-bitten form) is Quigley's doctrine of "future preferences" as the core

value of Western civilization, as any former student would instantly have recognized. As

Quigley explains it, future preference "includes the gospel of saving, of work, of postponed

enjoyment, consumption and leisure. Closely related to it is the somewhat different idea,

based on a constant and irremediable dissatisfaction with one's present position and present

possessions." This, for Quigley, was what distinguished Western civilization from the

"past preferences" of the Chinese (and their fondness for ancestor worship) and the

happy-go-lucky "present preferences” of the Africans. (In Tragedy and Hope Quigley worries

that younger generations of Americans were becoming "Africanized.")

By linking the professor with John Kennedy, Clinton made Quigley (another Boston Irish Catholic)

something akin to the intellectual godparent of his own public career.

The book that Clinton alludes to most often is Quigley's methodological work

The Evolution of Civilizations

(no doubt essential reading for anyone hoping to get a B); and the President specifically praises the

author for his clarity and aptness of expression. But during the very year that Bill Clinton was his

student, Carroll Quigley was finishing a book he had been writing for years. The book was the

magnum opus

Quigley expected would establish him as a major historian and a formidable thinker outside the classroom

and beyond the Beltway. And when it was finally published in early 1966, readers discovered that Quigley

had written the history of the twentieth century.

Tragedy and Hope was enormous: It weighed eight pounds, was more than half a million words long, and filled 1,300

pages plus index. It combined elements from Quigley's wide reading in economics, political science, psychology and

anthropology to create a general analysis of human development in nearly every corner of the world. Even the harshest

reviews noted how ambitious and interesting the book was, though none could wish it longer. During Clinton's senior

year, Quigley published an abridged version for classroom use.

None of this would be worth more than a footnote if it were not for the curious trajectory Quigley's published work

subsequently took. By 1972, Tragedy and Hope had excited conversation in regions far to the right of President Nixon,

and there were echoes of that excitement even in corners of the left. Quigley started receiving letters and phone calls

demanding answers to questions about the Council on Foreign Relations and the banking system. And after his death,

long after the book had gone out of print, entrepreneurial-minded ideologues were selling bootleg copies of his masterpiece.

One of these vendors was Robert Bolivar DePugh, leader of the Minutemen, a forerunner of today's angry militia movement.

Tragedy and Hope had indeed secured for its author a lasting reputation — well outside the classroom, far beyond the Beltway.

Twenty years after the author's death, it remains a classic text in the literature of conspiracy theory. One way to evaluate

this chain of events as a gross misinterpretation of Quigley's thinking: A few pages of

Tragedy and Hope were manhandled by

people whose pretzel-logic theories bore no resemblance to the professor’s sober prose and erudite theories. But deep in

Tragedy and Hope, near the bottom of page 949, Quigley mentions a "radical Right fairy tale" about" a well-organized plot

by extreme Left-wing elements, operating from the White House itself and controlling all the chief avenues of publicity in

the United States, to destroy the American way of life." With a turn of the page, Quigley makes a revelation:

"This myth," he notes, "like all fables, does in fact have a modicum of truth."

Many copies of Tragedy and Hope will open to this very spot — at the top of page 950, where Carroll Quigley proves...everything.

"There does exist, and has existed for a generation, an international Anglophile network which operates, to some extent, in the

way the Radical right believes the Communists act," Quigley writes. "In fact, this network, which we may identify as the

Round Table Groups, has no aversion to cooperating with the Communists, or any other group, and frequently does so. I know of

the operation of this network because I have studied it for 20 years and was permitted for two years, in the early 1960s, to

examine its papers and secret records. I have no aversion to it or to most of its aims and have, for much of my life, been close

to it and to many of its instruments. I have objected, both in the past and recently, to a few of its policies, but in general

my chief difference of opinion is that it wishes to remain unknown, and I believe its role in history is significant enough to be known."

It all sounds very sinister and is jarring when uncovered in a text written in a style of almost scrupulous dullness. Quigley, as an

author, loves to make lists and never says in one sentence what a paragraph will bear.. On the page, he lacks every bit of flare and

the aura that filled the auditorium, year after year, and made him a legend. Which is, in a way, evidence of just how devoted his other

students have been — the people with complex maps of influence and alliances among the rich and famous, who cite Quigley as the "insider"

who exposed the secret workings of power.

"When I heard that nomination speech in 1992, I almost jumped out of my chair," Phyllis Schlafly, a leading lady of the American right,

said one afternoon this fall, just after attending a Christian Coalition gathering addressed by Pat Robertson — that's the same Pat Robertson

whose book New World Order quoted Carroll Quigley as an authority "I thought, I bet I'm only one of a hundred people listening who know what

Clinton is talking about,” Schlafly continued. And what did did she think? "Well, it shows that Clinton, being a protégé, knew who the

powerful people in this country were. Clinton belongs to the Council on Foreign Relations, the Trilateral Commission, the Bilderbergers and

the Renaissance Society, and he was a Rhodes scholar, which I assume Quigley helped him with. Yes, Clinton is Quigley's boy.

"Now, look at the attractive Democratic candidates he ran against that year—Gephardt, Gore, Kerry. He had so much less to offer than they did.

I bet those guys must ask themselves, 'Why Clinton?' But I think it's pretty clear that Clinton had big money behind him. And he paid them back

with the Mexican bailout [last year]. The multinationals wanted NAFTA and GATT, and they needed help protecting their investments. Big money,

the end of nationhood, world government. That's in Quigley. That's what he’s all about.

At some point, viewing Clinton through the Quigleyan filter becomes habitual, and you notice things like the title of the President's 1996 campaign

book: Between Hope and History. One reflects that no sitting president in memory has had so much of his reputation subjected to conspiratorial

analyses while in office as Clinton. And yet this is the man who, as a student, sat in the lecture hall listening to one of the most prominent

conspiracy theorists of the century.

Quigley loved technological developments — for him the motor of history — and he liked to tell people how he was present at the creation of NASA.

Now one hears the news that the President has announced a space summit — which seems, then, to make sense in a new way. In search of other insights,

one picks up Quigley's posthumous masterpiece, Weapons Systems and Political Stability (which is 1,000 pages long and covers its subject only far as

the year 1500); or, more pertinently, The Evolution of Civilizations, Clinton's favored Quigley tome. One notices how deadly serious Quigley was about

projecting his methods of analysis onto the world as a political force: "Failure to use the techniques leads to childish judgments on historical events

just as, among practicing politicians, it leads to childish decisions in world problems."

And one wonders just how far Quigley’s executive-in-training embraced ideas such as this —

or if all Bill Clinton took from Georgetown and the classes of Carroll Quigley was a respectable

and rare B and an old school tie.

Scan of original article